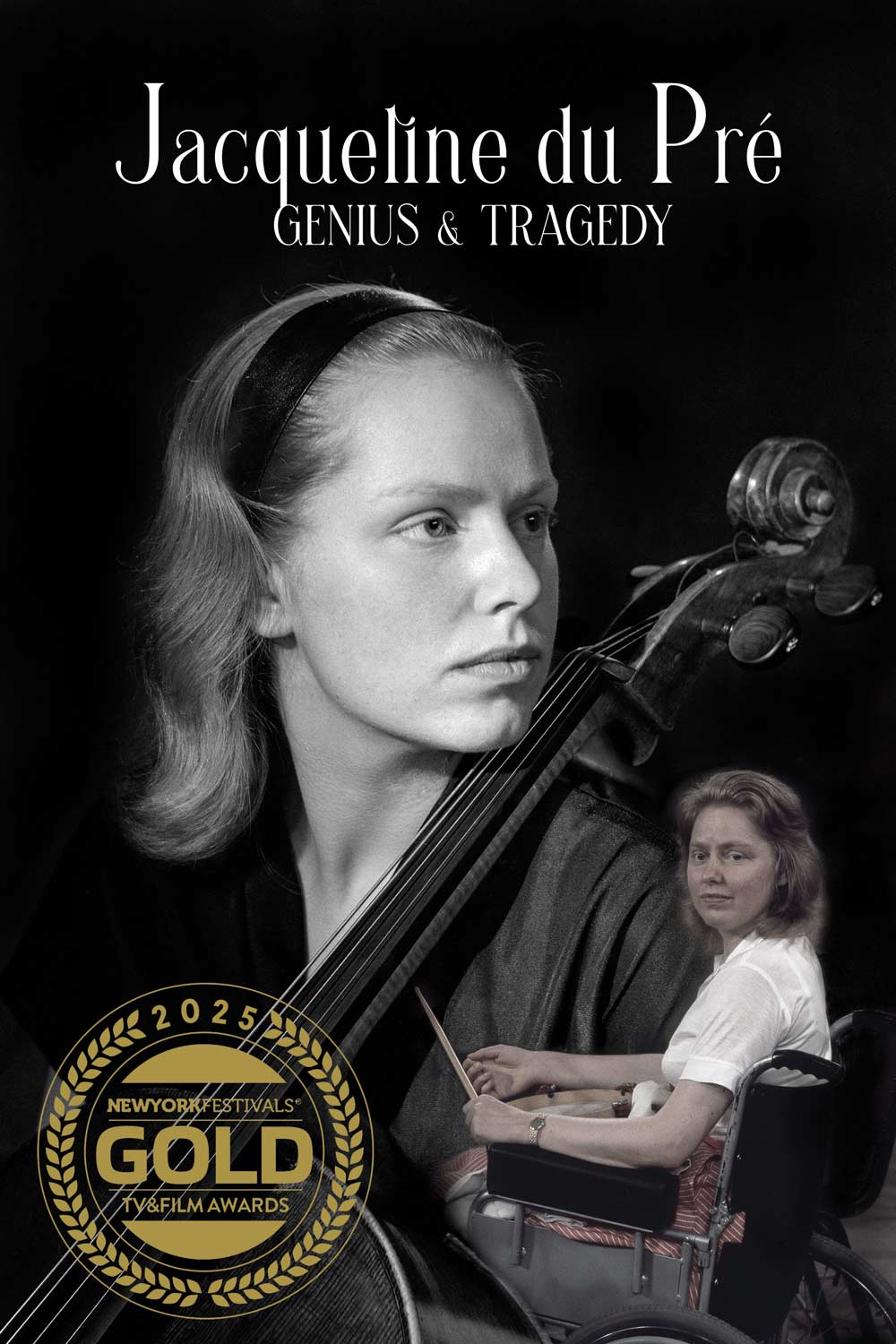

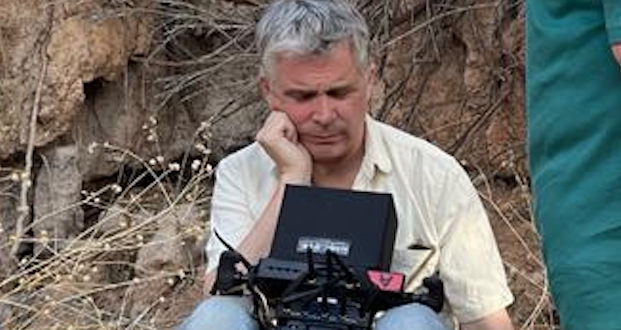

Yo-Yo Ma’s moving narration guides Jacqueline du Pré: Genius and Tragedy, PBS’s mesmerizing dive into the life of classical music’s most luminous—and tragic—star. Now available on KLCS|Passport, the documentary unveils the prodigy’s meteoric rise and heartbreaking decline with rare intimacy. We spoke with filmmaker Matthew Percival from his London studio, where he revealed the painstaking journey behind this poignant portrait, the legacy of Allegro Films, and what’s next for auteur-driven music storytelling and how PBS remains the last U.S. bastion for classical music programming.

What is your background or training and how did you come to do this documentary?

MP: I actually started as a marine biologist, so that’s what I wanted to do, I did biology, biochemistry at university. But I always had a passion for wildlife. When I was 20 years old, I was pretty convinced I was going to be David Attenborough’s producer for life. And that was what I was going to do; I lived in Belize for five months after university and I built a research center off the coast. The last week I was there, a cameraman from National Geographic came onto the island; he was making a film about reef fish, and he needed me to show him where all the best dive sites were. So we went diving, and I just thought, “Wow, ok so I can do natural history, but I can also do this incredibly exciting, practical work.” I can’t even remember his name and I wish I could, because he had quite an influence on my life, but I didn’t know it back then. But I changed tact, and I started thinking, “I don’t want to be a marine biologist and getting bitten by mosquitos all my life”, so I went back with an idea of getting into documentaries about animals. My step-father Christopher Nupen is a filmmaker and he had started Allegro films in 1966, so I had that influence going on as well. I joined a production company, it’s called Cicada Films, right at the bottom and I started as a researcher. I soon worked out that I had to learn to do everything. I wanted to do everything; I wanted to be a film maker, I wanted to make the tea, I wanted to do the research, I wanted to shoot, I wanted to use the camera, I wanted to edit. I set about teaching myself everything. So, if all the crew got food poising, I could make the film. And that’s the way I always went through my career. And it happened to me several times (laughs), where I had crew members go down in sickness in strange places in Cameroon and the Congo, and I had to pick up the camera and make the film. It always did me a lot of good to have that sort of philosophy. I worked at BBC, as a researcher, briefly, on the first Blue Planet series; I worked with Christopher my stepfather on his productions in my 20’s. My career is long and it’s not conventional, but I worked my way out and eventually got sent as a producer to California to make a series called Wild California. And then I joined CNN in 2004 and I was there for 15 years as a producer and executive producer, looking after a team in London; making non-news documentary content, often sponsored content on CNN – science, business, sports. We built up a big franchise of programs there, and then it was time to leave and I left CNN in 2020, just as the pandemic struck. I remember sitting at my desk, thinking “Wow, ok, this is new, I’m on my own. I have all this incredible experience, I’ve won some awards, but now it’s all on me.” And because it was the pandemic, I couldn’t shoot anything, I couldn’t meet anybody. So we’re in lockdown, and I had the idea, because my stepfather was sadly very ill, he had dementia, and he had a couple accidents; I had his whole catalog at my disposal, and I was now in charge of his catalog, or looking after it, or responsible for it, and so I \ proposed a film to the BBC, which was looking back at Christopher’s life. They initially turned it down, saying, “Lovely idea, but I don’t think we can indulge a long documentary around your stepfather. I call him my “stepfather,” but for all intents and purposes, he was my father, he came into my life when I was 12. But I persevered, because I had nothing else to do. The commissioning editor said to me, “Maybe we can add something extended to the news as a tribute to his career,” because he was at the BBC and did a lot for the BBC. And then, in the end, I just carried on. I managed to interview David Attenborough, Daniel Barenboim; I interviewed all sorts of people about Christopher. They all had wonderful things to say about him and I realized what an incredible story it was, because he began his career at the BBC roughly around 1966, so he coincided with the invention of the Arrowflex B silent 16 mm camera. For the first time in history, you could put a film camera next to a musician and record them without disrupting the sound. He was a musician at the time and he was friends with Daniel Barenboim, Pinchas Zuckerman, Zubin Mehta, Jacqueline Du, Vladimir Ashkenazi, Itzhak Perlman. And he realized he wasn’t going to be a professional musician, and he decided to turn the camera on his friends. He didn’t know it at the time, but they turned out to be the kind of godfathers of classical music. So he started making films. It was all new back then and very exciting – the idea of a classical music documentary. He combined performance with documentary fly-on-the-wall, and his career was launched in a very exciting way. So in the end, I made a 90-minute film at home; the BBC took a look at it, when they saw it, they loved it and took it. So that’s what I did in lockdown. And then I started a process.

How did I do the Jackie film?

Unfortunately Christopher did die. He did die two years ago; luckily he saw the film I made about him before he died and he passed away at the beginning of 2023. I continued. Now I was looking after Allegro films and I’d inherited this fantastic legacy of the programs. We have 65 films. And I went to New York to meet the commissioner at PBS to discuss the fact that our catalog and our films had never really been seen in the U.S. It was one of the only marketplaces that had never really seen our films. We have this wonderful catalog of maybe 70 productions, so I went to discuss it. And the commissioning editor said straight away, “Well, nobody’s seen Jacqueline du Pré here, we don’t know the story.” I said, “No, it’s true. Would you like a new film about Jacqueline du Pré for the American audience on PBS?” The guys aid, “Yes, let’s do it.” That’s how that came about, because of all the artists we have covered and have worked with us, Jackie remains the most enigmatic, and the most talked about. So we decided to embark on a feature length documentary that used all the best of the Allegro catalog that we own. I don’t know what percentage of Jacqueline du Pré material we own, but it’s probably quite high, because Christopher was a great friend of hers to the end, was there when she died. So I set about thinking I’d combine some of the previous material and sequences, but it soon became apparent that I’d have to unpick everything that had been done before and start again, because it was really the only way to do it. And we decided to involve Yo Yo Ma pretty early on, because he’s now using her cello. He has her famous Davidoff Stradivarius cello on loan. He also met Jacqueline du Pré a couple times and had a couple lessons with her, and spoke very intelligently and intuitive about her. And he was the perfect person to do it, and I don’t think he’d ever really narrated a documentary. He’s done lot online and he’s done lots of television, but this was something a little new for him and I think he needed a little persuasion, but I knew he was the perfect person.

He was absolutely the perfect person. He’s got a lovely story-telling voice, and he has a deep personal connection to Jackie.

So I went to Boston to see him, home of the Boston Symphony. And he did the introduction and the narration. And actually there’s a lovely point in the film where I had the idea that he’d just start the Elgar cell concerto for us, and then take us into the opening sequence. And I was terrified about where to make the music cut to transition from his performance and interview to Jackie’s performance. But it worked beautifully. When I got home into the edit, I was very happy, because it was always the cornerstone of my opening. So that’s how this came about. One – we had this incredible archive, two – I had a deep personal connection to Jacqueline du Pré through my stepfather, and then we had the meting with PBS where they expressed an telling that story for their audience.

I love how you have the old footage like you said, from the files, but also included new footage like the interviews with Daniel Barenboim and Itzhak Perlman. Is that because you knew you needed to close the circle and have something new?

MP: PBS obviously they wanted something new and I didn’t want to just recycle what had been done before. So, we had to try and do something new. And there were some things to do. I went back to all the rushes and I found camera angles from certain performances which I got digitized. I had great difficulty syncing up the sound in some places, but I managed to bring back some different angles. I went back to interviews for some different insights from people like Daniel. In fact, there are interviews from Daniel Barenboim from three different decades. It was important to do that. It brought it up to date; it gave someone a face and a modern figure of classical music to relate-to.

The other big thing was the interview from Jackie from 1980 when she was ill. That had been used on a DVD, but my stepfather never wanted it broadcast because he felt it didn’t really do her justice and because she wasn’t well. And he always felt the interview wasn’t her best interview because she was clearly suffering a little bit. But when I watched it, I didn’t have that perception. I wasn’t in the room when they did that interview, so I was coming at little bit more objectively. I thought it was amazing. I thought it was a beautiful interview and it should go into the film, and it is also a very poignant transition. A lot of what I am and what I do is from Christopher and what he did and what he taught me, so the fact he’s not here to see this new Jackie film is very sad, but I know he’d love it. I know he’d be very pleased it was going out on PBS. And, the other thing that was never in the original films was a representation from Jackie du Pré’s caregiver, who was Ruth Ann Cannings. She was a remarkable woman. I had an interview from 2000 to play with, which hadn’t been aired before. And then I thought it was also very nice to see if she was still around today, so I reached out and I found her. And we did a sequence in the cemetery where she was visiting Visiting Jackie’s grave, so it tied it to the modern day. She was an amazing woman, as Zubin Mehta says in the film, she looked after Jackie like a sister. And I think she had a tremendous impact on the last 12 years of Jaqueline du Pré’s life. So, we did have these new ingredients. And I also wanted to get some younger voices into the film. There was a lot of people over the age of 60, because those are the people that remember her. Sheku Kanneh-Mason and I felt that was a really important interview.

Was that the black cellist in the film?

MP: Yes. He’s a fantastic cellist and he’s very much the cellist Du Jour. He’s very popular and he’s doing incredibly well. And, of course, it wasn’t surprising to hear him say, that even though he’s a 20-something year old, Jacqueline has a defining influence on him. He tells a story which isn’t in the film, of travelling down on holiday in his parents’ car and being completely mesmerized by hearing Jacqueline du Pré on the radio; he never forgot it. So her legacy and her influence on young musicians today is phenomenal, considering she had such a career and she dies in 1987. It’s incredible. Of course when we went to the grave, there was a flowerpot and a note on the grave written by an 11-year old, about how inspiring Jackie was to her. So, she had a tremendous long-lasting impact.

I re-watched it over and over; I felt it could have been a longer film. Is there a longer version you can release directly, like on Amazon? Did you feel people wanted more?

MP: These days most people want short, so, selling a 90-minute film about a British cellist who died in 1987, I was pretty pleased with that. Most people want short, short, short. I tried to let it breathe, but I also have to be honest and tell you I think I exhausted the material we had. I could have probably made it a tiny bit longer, but I don’t think it would have been better. And there was a finite amount of stuff shot with her, unfortunately. I wish I could speak to Christopher now and go back and say, “Why didn’t you shoot more?” There were relatively limited documentary material around her.

Well, there was a lot; he did shoot plenty of her walking the London streets.

MP: Absolutely. Thankfully he did, because otherwise we wouldn’t have that record. And obviously, you know Jackie. When you see her play, you understand, you understand straight away what was so special about her. But you know what? The shots of her walking down the street, crossing the road, with her dressmaker, they also really are important, because they’re telling you about her vivacious and open, innocent personality. Everybody you speak to about Jacqueline du Pré, and I never met hers sadly, says that she was a dozen different people. She was a very complicated character to understand. She exuded tremendous confidence on stage. Musically nothing was beyond here, she could play anything, do anything. But she was clearly, like all genius protégés, they can be socially awkward, we call it perhaps “on the spectrum” today. It’s a bit of a cliché and easy term, and I’m not saying that Jacqueline du Pré was on the spectrum, because it was before diagnoses came-on. But they can be awkward, they can be withdrawn, because they’re operating on a different level than most people. And therefor they find friends of, their own age, hard to come by. And Jackie was a classic example of somebody that was also consumed by her talent from the age of four. In some ways when you have talent like that, it dictates to you how your life goes. It’s so powerful, and of course the passion that goes with it, it’s so powerful, it draws you into a path. And you can ignore it, why would you?She had an unusual upbringing. And when she was very young, I think she found friendships difficult with children her own age, because she was already at such a musical level. Her mother did a fantastic job of harnessing her talent. And I think she was very aware right from the start what her daughter was capable of, that she was dealing with something quite special. But she says in the film that she was quite naïve about a lot of things in life because she, perhaps, lacked some social interaction that a lot of kids have up to the age of 15, 16. And she was quite famous, people used to think she was lacking in common sense, or knowledge, she didn’t know what the capital of Norway was, or how much a pint of milk cost. But when it came to the important things, she had incredible intuition and knowledge. For Daniel Barenboim to say he learned more from Jacqueline du Pré about music than anyone else, that’s an extraordinary thing to say. She found her milieu, she found her level, when she met Daniel Barenboim and all these artists.

Are you into music? Are you a classical musician buff, do you listen to it in your own time, and do you play any instruments?

MP: Yes, of course, I’m into classical music; I love classical music. I don’t play an instrument. Which by the way, I’m 53 years old and I still intend to correct this problem. I would love to play an instrument and I will one day find the time to learn and get lessons. I love classical music, it was something that didn’t come naturally to me, it had to be something I was introduced to, by repetition and by spending time with the Allegro catalog and thanks to my stepfather I have pockets of deep knowledge and then I have huge pockets of no knowledge. So I don’t prescribe to be an expert or a music buff, but I have a deep appreciation for it, and a love of It, and it’s something that I continue to work at.

What did you learn from making this documentary?

MP: That’s a good question. At a very personal level, for me it was a great reinforcement of what I learned in my career, because it was very difficult to unpick sequences that have given a lot of pleasure to audiences already, that were shot in the ‘60s and ‘70s and had gone out in previous films and re-edit them, and also to blend in new material with old material is not easy. So, that was a challenge and I learned something from it in terms of what’s possible and where I had great doubts at the beginning, it all came together in a way that I was extremely proud of.

I thought I knew everything there was to know about Jacqueline du Pré, but I guess spending a year of my life with her, again, gave me a whole new insight into just complicated but, how much she touched people and how extraordinary her talent was.

Did you hear from Jacqueline’s family?

MP: No, I didn’t actually; I hoped they watched it and they liked it. There’s a complicated story with the family. Some people criticized the film for not talking in more detail, but I have my side of the story which I have from my stepfather and those people that knew Jackie best. He was very, very disappointed that the feature film “Hilary and Jackie” was ever made, and everybody that really knows Jackie was upset by that film because it gave a very deceitful and dishonest version of who she was. And I think, if you watched the film we’ve made, I didn’t presume to tell people who Jackie who was, I let other people tell that. And there was a mystery to her personality, I just let the footage do the talking. If you watch that film, you understand Jackie. People who knew her said there wasn’t a bad bone in her body. And so, I have a responsibility, and as custodian of a lot of that footage, I’m very careful about how it’s used. And I want to make sure that she is remembered in a way that I feel she should be.

I did notice that you steered away from most of the early 1970’s scandal about her, but still addressed it; or at least conveyed a sense that you dealt with it. It seems to me, the shock of her diagnosis was, in-part, a factor.

MP: Completely. When she’s sitting on the trains, with the newspaper headlines, there’s a pretty clear nod to that episode and that period. I didn’t want to completely ignore it, because as a journalist, I think that would have been wrong journalistically. And yet, it’s a lot more complicated and nuanced than people understand. Most people think that she was in a pretty bad way, and really suffering because there was a period where she didn’t know she had multiple sclerosis. She had a mystery illness that some people put down to neurosis, that she was being a neurotic artist. She had symptoms a lot earlier than people understood. If you imagined how extraordinary her playing was, and then it started to disintegrate. She started to lose some feeling, she started to do things she couldn’t explain. She was deeply troubled by it and there were certain people who took advantage at a time when they shouldn’t have; when that whole affair scandal broke. So, that’s the story I know. Some people may tell you a different story, but I’ve heard six, seven, eight people who knew Jackie intimately tell me the same thing separately, so that’s the side of the story I choose to follow, and quite frankly, I don’t really care what she got up to. My job in that film was to tell you about Jackie the artists, the genius, and the sadness of what happened to her, the tragedy; which is why we called it “Genius and Tragedy.” Had it been for another network, they might’ve wanted all that in. But for me, I wasn’t concerned with it. It’s not the best thing about Jackie. It’s not the thing that people need to know about her.

Will there be more classical music documentaries? There are not many people making these films, in a relevant way; PBS being the outlet in the U.S. for arts and classical music, there’s likely interest in, maybe, Itzhak Perlman, YoYo Ma?

MP: Absolutely, we are open for business. I’ve got great hopes that we can continue to maintain the Allegro films brand and make classical music documentaries that tell, ultimately, human-led stories about people who are talented. Young talent remains incredibly fascinating and intriguing. But it’s not getting any easier to make these films. The truth is that the proportion of television slots and time given to the arts has gone down and down and down with the impact of mobile phones and social media. For small, independent production companies like us, it’s getting harder. It’s getting more expensive to make and more complicated in terms of the way you deal with artists, agents, record companies, new platforms. But, as Christopher used to say – “When you’re in trouble, you invent things.” So, it’s up to us to invent new formats and new ways of bringing music to audiences. And there are some interesting examples even on the BBC, who’ve really taken commissioning down a lot. But there are some great examples of drama documentaries now, which are a mixture of drama reconstructions, and narratives around the likes of Mozart and Jane Austen. They’ve done a film about Daniel Barenboim in his own words. So they are out there, you’ve just got to use all the modern techniques available to tell those stories in new and interesting ways that are engaging. And maybe it’s always been like that. Maybe it’s always been difficult for independent producers to make classical films, but it does seem particularly difficult right now in this economic environment.

It sounds like Allegro Films is unique in that way.

MP: Yes. We’re unique because we have a back catalog stretching back to the 1960’s, but they’re all retiring. And it’s an interesting place to be because people will want to remember them when they’re not here anymore, so that provides new opportunities. We have this catalog, which is a reference point, but our goal is to make new films, and we have quite a few ideas in the pipeline. So, we’ll see what comes up, but I’m very grateful to PBS for supporting the Jackie film because it was her 80th birthday this year; we made the film for that historical peg as well. It won two gold awards at New York festivals this week in the music and biography categories.

Is there anything specific in the pipeline that you are working on?

MP: There’s a film I want to make called “Strings of Freedom,” which is about a double bassist called Leon Bosch, who’s had a remarkable career, and next year is the 50th anniversary of the Soweto uprising n South Africa. He was arrested as a 15-year-old, and beaten in that period. But he went on to become one the world’s best double bassist. And my plan is to take him back to South Africa and film some sequences there going back home and also he’s now conducting. He’s a remarkable man and I want to make a film about him, so we’re trying to raise the money to make that film. And I’ve got something in the pipeline which is drama based, but it’s re-enactments around the conception and genesis of great works of art. So – Chopin’s preludes for example, were written by Chopin in Majorca in the winter of 1938-39. And that’s a remarkable story. He was on the island with George Sand, the writer, they had a 10-year relationship. But they had a terrible time; then he died. During this whole story, he wrote the preludes. Its an example where you can tell a great story around a single work. But nothing confirmed.

What about Daniel Barenboim? I love his orchestra, the West-Eastern Divan Orchestra’s Beethoven’s Ninth. Have you thought about working with him more in-depth?

MP: Yes. I don’t know if that moment has passed, or to what extent Daniel is semi-retired now. Although you’re absolutely right when that orchestra was conceived, especially when you consider the political environment we’re now in, in 2025, the idea of that orchestra is still so powerful. I wish I could go back in time (laughs) and make that film because I think that would have been a fantastic film to make. He’s done a lot of documentary stuff around it, it’s a project I know he’s extremely proud of. I’m sure my stepfather felt the same thing, that he’d wished he could do more stuff with Daniel. I’ll tell you what we did do – being in an edit suite by yourself, wondering what you’re going to do next, I found these full episodes that were recorded in 1967 of Daniel Barenboim talking and illustrating on a piano, about Beethoven. He wrote a series with my stepfather called “Barenboim on Beethoven,” some of aired in 1970, which was the 200th anniversary since Beethoven’s birth. So 2020 was the 250th anniversary, and I found all this material and I brought it all back from the scripts narrative, and I produced a 13-part series of Daniel full of enthusiasm, it was wonderful just him playing and talking about Beethoven. It was riveting stuff. I found old one-inch tapes, and Channel 4 in the UK broadcast it, so that was a fantastic project as well. And that was a really great thing to do with Daniel, because when you see him, when he was that young, I think he was only 23 years old when that was made.

It’s funny, because in the clip that you showed I the documentary, when they were all fooling around in the young years, he was fooling around and he was playing the intro of the fourth movement of the Ninth. I wondered why he did that and that he must have liked Beethoven. I don’t know if anyone caught it, but no one seemed to care; I figured he must like Beethoven!

MP: (laughs) When was this? At what point was that?

I’m going to have to find I and then email you.

MP: Yeah, you must. I might have missed it.

I recently saw Itzhak Perlman playing Bach Partita in D Minor on YouTube from eight years ago, old concert footage. You guys were ahead of the curve in putting things on YouTube back then. It now has over 2 million views.

MP: YouTube is a constant conundrum for us. We’re very proud to have 107,000 subscriber, but we’re still in this world where we have to try and maximize the value of our archive. So if you put it on YouTube it becomes less valuable to broadcasters. At MIPCOM his year is a classic example – it’s like there’s only one channel on the planet left and it’s YouTube, YouTube, YouTube. And that’s great, but it’s very difficult to know how to give as much as you can on YouTube, but withhold something back that keeps a little bit of the archive secret or mysterious, or valuable. So it’s always a problem. It’s a big job to grow a YouTube channel and it’s not for lack of resources. My plan is to give the YouTube channel a lot of love this year because it’s very valuable. Those subscribers are whole new audience. They’re not passive, they’re interactive, and very valuable, very knowledgeable. It’s a classic case when you have a niche subject like classical music that your YouTube audience is incredibly knowledgeable and incredibly enthusiastic; and that’s really important. They’re a very, very engaged audience. I’m always tempted to go in and reply to people personally, and I can spend the whole day doing it, but I try to pull back (laughs) Let the community do its thing.

What is your typical day like now and are you working on anything new?

MP: In terms of classical music, I’ve got this potential series of documentaries around the genesis of great works of art. That’s not just music, but it might be sculpture, buildings, architecture, painting, lithographs. I’ve got this film about Leon Bosch which I’m very excited about. I know it’s going to be a beautiful film, if I can raise the finance to make it. He’s an extraordinary character, a wonderful man, and a beautiful musician as well, an incredible musician. And then our brand is classical music, but my background Is natural history, it’s conservation, it’s science, I’ve done sports. So we’re staring to think about broadening our reach, as a way forward. Classical music will always be number one, but if you can make really good classical music films, it doesn’t mean you can’t make good films about other things. I have other passions, I have passions around natural history, conservation, the environment, especially right now. And sustainable business, in particular, is a topic I’m interested in, and sports. So I’m looking for ideas around those topics as well.

[This interview may have been edited for clarity]

Don’t miss this exquisite homage to a legend whose genius still echoes. KLCS|Passport members can stream Jacqueline du Pré: Genius and Tragedy or on the PBS App.

To learn more about the documentary film visit AllegroFilms.com or the film’s PBS page.

To learn more about Matthew Percival and his current work, follow him on Instagram.