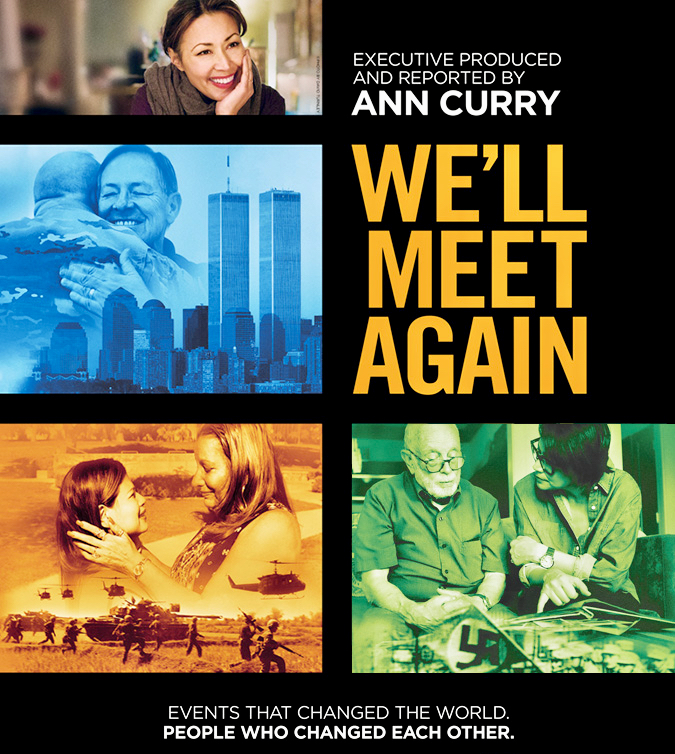

After her high-profile departure from network news, Ann Curry didn’t fade from the spotlight—she redefined it. From her poignant PBS series We’ll Meet Again to illuminating turns on Finding Your Roots and Arts Talk, Curry has carved out a space where storytelling transcends headlines and connects on a deeper, more human level. Now, in an exclusive conversation with KLCS, the veteran journalist opens up about her well-received PBS venture and the unexpected journey that led her to public television. For Curry, it’s not just about reporting the news—it’s about telling stories that endure.

Ann how did the idea of “We’ll Meet Again” originate and what was your path to making this series for PBS?

AC: I was invited by a production team, and specifically a person who was running it, to participate, and I’m not really sure if PBS had a hand in inviting me, but this originated in the minds of a production team, a bunch of young talents out of Britain. They were interested in this idea of finding people who were caught in these stories. I think because so much of what I did with my career was to interview people when they were caught in these stories, that were really caused by world events. When world events catch you, they catch all of us. It caught out ancestors and they catch us now, these world events that change where we live and how we live, how we’re impacted by all the things around us. This idea is actually the big story, the story that doesn’t end. So when I heard about this idea from this production team and PBS, it resonated with me because it would allow me then, to essentially tell the rest of the story. I, often, when it came to documenting news events, whether it was a war or humanitarian disaster, or any other movement, protest, I was always there when it was happening. So, to be able to then go find the people long after it happened and asked them what they thought about it, having had time to really think about it, was a great gift. And not just because it was lovely for me as a reporter, but also because, of course, they had time to really process it. These people who were caught, and they were able to talk about it with perspective and, I thought in many cases, in a really beautiful illuminating way. So, I love doing the series. We did 12 parts over two years; it was a 12-part docuseries. It was amazing, I thought we could have done it during Covid and found amazing stories. We could do it now looking at what’s happening in our economy, or in our politics, there’s so many ways to do it now. We could do it about the Korean war, or in Israel, and in Gaza. There’s so many subjects we could talk about. We could talk about the changes in America, women no longer being able to feel some guarantee over their reproductive freedom. There’s so many ways we could look at events that were unleashed by powerful people, generally, or powerful events, and how they impact everyday people who just get caught, get swept up by these events. I think these stories tell us about our abilities to survive, and also to help each other. And to find peace in the end.

Was there ever talk about a third season, or more?

AC: Yes, there was talk about it. I think that there was some funding issues at PBS, so that played a part in why we didn’t continue. It’s a big logistical thing to try to pull people together to do[the show]. A lot of this depends on research, finding the people. You find the story and then you spend a lot of time trying to find the people in the story. And we got enormously lucky, there were 12 episodes. I think we could have done more, certainly, but there’s a line “Don’t be sad it’s over, be glad it happened.” And I certainly am glad it happened.

Was it hard to find the people and do the research for that? Was that a challenging part of the process?

AC: Absolutely. We had a team of people specifically focused on the research. And it took, really, months of calling and calling, and searching through databases to find people who, first of all had stories to tell, and second of all, were comfortable being interviewed. I don’t know that it’s hard to find these stories, but we wanted to find stories that would really resonate. It’s not hard to find stories of people who were affected by world events, but for example, to find the boys who were caught in World War II and were forced to go to Dachau. And to find those two boys, track down their story, a lot of it is looking at what’s been written, to some degree there’s also a matter of luck, in terms of whether you can find these stories.

It’s a great idea for a show. Was there a kernel of an idea they had when they approached you?

AC: I don’t know if there was a particular event, I think that my working with the team and helping shape what it ended up being, the conversations were really about honoring the people who were willing to come forward with their stories, because oftentimes the subject matter wasn’t easy. These interviews weren’t easy. There is a wish to thank the person who rescued you – emotionally or physically – when you were caught, when you were swept up by a world event that you didn’t see coming, and you weren’t prepared for. Sometimes, who you want to thank is not someone whose name you remember, because it happened so long ago. Sometimes, it’s a person who you only spoke to for a brief time, or maybe, who you didn’t say much to at all and who didn’t say much to you at all. But, what they said was so consequential that it changed the course of your life. So, I think that’s the thing. The idea that we don’t get through any of this by ourselves. Sometimes it’s because of the people we know and love, and sometimes it’s because of people who we don’t know and whose name we don’t remember that we’re able to get through it. So, to highlight that idea, I think all of us watching the series or thinking about this idea, can probably think about someone we should thank. Someone who, “I hope that person is still alive” or “I wish I could track that person down”, and just tell that person, “You know, I really loved what you said to me all those years ago,” or “I love that act of kindness you showed to me, and thank you.”

I always say, “We are angels on each other’s paths, or can be,” and I feel the show says that, without saying that.

AC: Mr. Rogers, another PBS’er said, “Look for the helpers.” It’s true and I think this idea of looking for the helpers.

When I heard his line, I thought – What about also offering to help, be a helper?

AC: Oh yes, to be a helper. Actually, it’s the most selfless thing you can do, because you can feel so good for having done so, even anonymously, and maybe especially so.

Some episodes I connected to were the Equal Rights Amendment’s early women’s rights years, because that was a special time for women, the September 11th reunion of the photographer’s assistant and the man from out of town, the people reuniting during the early years of the gay rights movement. Did you have a favorite episode or ones that resonated with you?

AC: I connected with all of them. I think the young girl who was sent to an internment camp during World War II because her family was ancestrally from Japan, being treated with great kindness by a fellow student, who was not Asian, was incredibly touching; to see the two now grown women together and acting, really, as if they were still in elementary school when they were talking.

Those events of our early years as we’re starting out on life’s path, they leave that familial indelible feeling, untouched by the different paths we take in life. Did you feel that they all had a special connection in that one moment in time? Because it looked like time vanished when they came together again.

AC: It’s as if when they reunite, that, no time had passed at all. Suddenly, there was the story of two children, who met again, having splayed as children, and met now in their 70s; and they were acting like children. They were giggling, and I mean that with enormous respect. In other words, it was as if seeing each other had unleashed this kind of ability to be joyful, in a silly way. I think you’ll see, especially because many of the people you’re interviewing were in their 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s, all of a sudden their faces got very young again. There was like a brightness in their eyes, and a joy in their expression. You’re absolutely right, there was a sense that time vanished that no years had passed at all, because people who knew you then, know you in a way that no one will be able to know you, because you were the same person, but there was so much life that you hadn’t lived yet; you were this part of the same person. So, when you see that person who knew you then, in that way, you can be that person you were, without all the other stuff, because you know you can be seen that way by this person. Absolutely, everybody got younger. And happier.

Yes! And only those two souls had that special moment; no one else had the experience of their memory. No one else was in that memory, just those two people, from 50 years ago; that’s why they were thinking about each other.

AC: See, this is the thing…this is the interesting thing. We unleash things in each other. We meet someone and that person happens to say the thing in us that makes us think something, feel something, that makes us decide to go a different path, or maybe even just a little bit of a different step.

You’ve been in other PBS shows, and taking Lidia Bastianich, who I’ve interviewed a few times, to a downtown Japanese market where you shop to buy foods that make you think of your mom.

AC: Yeah, that was some time ago. What you probably don’t know about, I participated in a documentary that’s coming up that’s part of the series “American Experience” for PBS. This hasn’t been aired yet, I think it’s just in the last throes of editing. It’s called “Bombshell” and it’s a documentary about how the US government intentionally misled the American people about the true impact of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki for years. And how it hired a New York Times journalist to actually tell the story in a not true way; and how it took another journalist, years after the bombs dropped, to finally tell the truth. His name was John Hershey and he wrote the book Hiroshima. But until then, many Americans, they were given to think that there was not the kind of radiation sickness impact; that it wasn’t, in fact, what it is, which is a chemical weapon. That not only is it a huge bomb, but it’s a bomb that leaves generational impacts and disease. This was pretty apparent pretty quickly, but this story was not only squashed, the American public was purposely misled. I participated in this because I am very interested in the struggle to insure that there are verifiable sources of information, not just in American, but in the world. I think that this is an early example, and one of just many, really, across the world that shows us that truth is always vulnerable. There are so many reasons why people don’t want the truth to come out. So, this documentary, looks like the premiere is actually going to be in Hiroshima sometime in August. So it’s coming out as part of American Experience.

How did you get involved in all of these PBS shows, is it because you’re in the PBS family?

AC: I think PBS does quality work. So it’s hard not to be involved in PBS projects if you want to do quality work. And, absolutely, I think there’s some really wonderful, illuminating, historical stories. I love “Finding Your Roots,” I think that it’s fascinating to think about our ancestors, because it’s a window. It’s not just a window into you and your family, it’s a window into what happened in the world, in history. And it’s very similar, it’s the other side of my series We’ll Meet Again, because it’s actually taking you and your story to the world events that shaped why you’re in American, where your people came from and how they moved to survive.

What fascinated or moved you the most about appearing on Finding Your Roots?

AC: Well, there’s one very simple answer to that. I did not know the name of my grandfather on my father’s side, and I had been searching. And I searched while my father was alive. He desperately wanted to know who his father was. He was born in those days, they called him “illegitimate;” he was an “illegitimate” child. And it was very painful for him. And I remember he was sick and dying of cancer, but he was still asking. And I had been researching and researching and finally I asked him to submit a sample to a new website that was called “23 and Me,” it was brand new at that time. And we submitted a sample and they couldn’t determine who his father was. But after the broadcast, after I found out who my grandfather, my father’s father was, I went to my father’s grave and I took a bottle of wine and a blanket. I had all my brothers and sisters there, and we spread the blanket and I had a cup and I poured some wine into the cup and I poured it over my father’s grave and I said, “So daddy guess what? We now know who your father was. So, don’t worry, our children will know. And we don’t have to be alone anymore.” And we told them all those things, a lot of it weepy-eyed, but I know he would have been so pleased to know that we actually were able to find out; it was very meaningful. Dr. Gates was very interested in talking about the Japanese side of my family, because there’s a whole bunch of history there. But I thought, with this opportunity I really had to find this out. I got very lucky. I didn’t find out that my grandfather was anyone important, in fact I found out that he got in some fights, and he was a bit of a ruffian. He was a railroad worker and struggled, and that he fathered my father out of wedlock, but still, my arms are open to him, and to welcome him into our family, because he gave me our father. So there you go.

It sounds like that episode was a blessing; you were able to or close the circle for your father.

AC: A hundred percent. And, also, I did find out a little bit about my Japanese side that I didn’t know. I knew that I was from a long line of farmers, and also Buddhist monks and priests, and that the village where my mother grew up, her ancestors are traced to have been for 400 years, farming rice in Yamagata, which is a very good place for rice. But what I didn’t know, which I found out from Dr. Gates and his team, is that during the Meiji restoration, when all things foreign had to be rooted-out in the country, including Buddhism, my ancestors buried the huge statues in the village representing the Buddhist faith. I think one of those statues was of Jizo, who is a Bodhisattva. I don’t know very much about Buddhism, but I know just enough be dangerous, but having been raised Catholic by a Buddhist, I have a little bit of knowledge. So they buried these huge statues so they wouldn’t be destroyed. So I plan a trip to Japan very soon, possibly as early as this year; one of my interests is to go find those statues that were buried all those years ago.

What have you been engaged with as of late? What is a typical day for you now?

AC: My days vary from day to day. But what I’ve been doing lately is, I’m a fellow at Yale teaching journalism. I go to New Haven to the Yale campus for weeks, a week at a time, and then come home. When I’m there, sometimes it’s three or four days at a time, but it depends on the visit, I’m meeting with professors and students, and really fundamentally I’m focusing on talking about journalistic ethics. Yale does not have a journalism degree, but the university makes a lot of journalists; makes a lot of good journalists. In fact, John Hersey and Bob Woodward went to Yale, and David Brooks went to Yale. So a lot of good journalists come from Yale, but the struggle is that it takes much more than an ability to write, or to ask questions, or to take photographs, or to make a movie, to make a journalist. It takes an idea about who you’re actually working for and why. And it takes some skills in how to vet information and make sure that it’s verifiable, and the responsibilities involved. So, I’ve been really enjoying that. I have office hours with students; in fact, a student wanted to meet with me today, but I said I’m meeting with you, so I’ll meet him later this week. [I’m] really trying to counsel and encourage students to be thinking about how to think about information. So that’s happening. I’m also a high-profile supporter for UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees), which is the refugee agency, because I want to help people who are fleeing war and persecution. The suffering, I think, is hard to sit back and watch. That’s about interviewing and about trying to document things, and making remarks. It’s kind of like being a high profile reporter, not a high profile supporter, because essentially I’m doing the same job, and I’m not doing it in a paid way, in fact I won’t be paid for that. So I’m doing it as a volunteer effort, because I want maintain my independence. And I’m also doing a lot of speeches, I say “Yes” to virtually every ask, when it comes to speeches, lectures, events for women. In fact I was just on a Zoom, there’s project for Equality Now that I’m involved in. I just get pulled into these projects for women, for people fleeing war and persecution, and for journalism; and that’s been my focus. I’m also writing memoir, but, you know, that takes time. (laughs) And a lot of ahh…emotional struggle, because it’s hard to write about yourself.

I believe keeping a journal is a good idea, so you can transcribe when you’re ready!

AC: Yeah, although a lot of things I write in a journal maybe should not end up in print. (laughs)

Do you miss being on TV or doing TV regularly? Or, do you enjoy having more of a leisurely schedule?

AC: I have to say that the one thing I do miss, is…I miss being able to make sure that stories that really matter are covered. I miss being a voice in the fight to amplify the voices of people who deserve to be seen and heard. I think there has not been enough of that kind of reporting in America and overseas. To some degree that’s because news organizations have been shrinking because of the economic fallout from the rise of the Internet, and in part, that’s happening because of journalism’s self-inflicted wounds which has some news managers making decisions that are better for the bottom line than, necessarily, for the illumination of their readers and viewers. So, that I do miss. I miss that, because I think that, really, ultimately, was the real job I did. All the other stuff, being on camera, was something I learned to do because I had to do it. I did enjoy a lot of parts of it, but I was somebody who never really, necessarily, wanted to be on camera; I was somebody who wanted to ask questions. I was somebody who cared about people, honestly cared about people, and wanted to make sure that people who had stories that deserved to be heard, had a chance to be heard. That’s really what I did. I did whatever I needed to do to make that happen, including, learn how to put makeup (laughs). They actually sent me to makeup school! I remember I came back, it was in local news in Portland, Oregon, and I came back from having done a report and the new director said, (raises voice like the news director) “Ann, you’re never going to go back on television until you get some makeup lessons! I’m going to send you to makeup school!” And I said, “Well there isn’t a makeup school around here.” “Well, I’ll find something!” And sure enough he made me go and learn how to put on makeup. Yup!

My escape on weekends are the British shows on PBS like Call the Midwife, Marlow Murder Club, my new Downton, and I get to watch for press access, before they’re airing, like I plan to watch all Grantchester this weekend. Do have any favorite PBS shows you enjoy escaping into?

AC: I just recently watched the one about Jane Austen’s sister.

Yes! Yes, it was good! (Miss Austen is available to members on KLCS|Passport)

AC: So good! I loved it. I binged watched it. I’m a bit of a Jane Austen-file. And I’ve watched the Keira Knightley Pride and Prejudice four times, and of course I watched the other ones as well, but that was one was particularly good. So yeah, I’ve enjoyed it. I watched all the one about the priest.

Grantchester? The one I’m going to watch this weekend?

AC: I’ve watched every single one.

Marlow Murder Club* you’ve got to watch it! Have you seen it?

AC: No, I haven’t yet. Is it about murder?

It’s about three women who investigate a series of murders in an English suburb. The writer of the series (Robert Thorogood) lives in Marlow and that’s where they shoot the show. You’ve got to watch it and let me know what you think!

AC: Okay!

I have like the jollies, it’s my new Downton, and I wish it were more than four episodes. These three women are from different places in society in the town of Marlow; it’s wonderful.

AC: Wow! I love that. I love that, it’s fantastic.

If you need to escape.

AC: We all do, don’t we? I mean we’re in a time when everybody seems to be wanting to escape, so, absolutely.

Anything you’d like to add?

AC: No, you’ve asked some really good questions. I guess only that I think that PBS has been very important in creating wonderful content, and I cheer-on everyone at PBS and encourage them because what they’re doing is really important, culturally, for America.

[This interview has been edited for length and clarity.]

KLCS Members can stream We’ll Meet Again on-demand, anytime, on KLCS|Passport.

You can follow Ann on her social media: Facebook, Instagram or X/Twitter.

*Season 2 of The Marlow Murder Club premieres Wednesday, September 3 at 8 PM on KLCS Public Media.