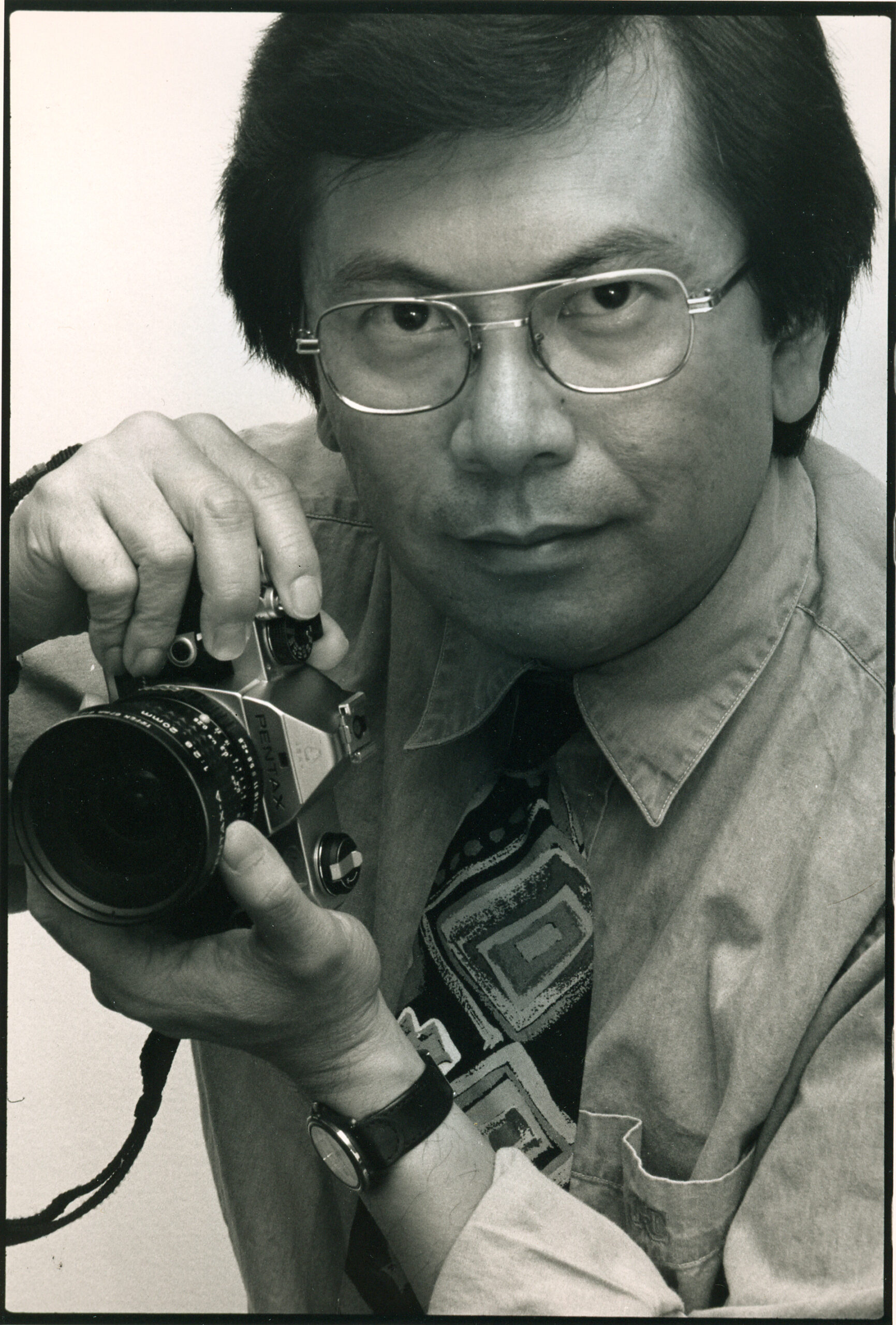

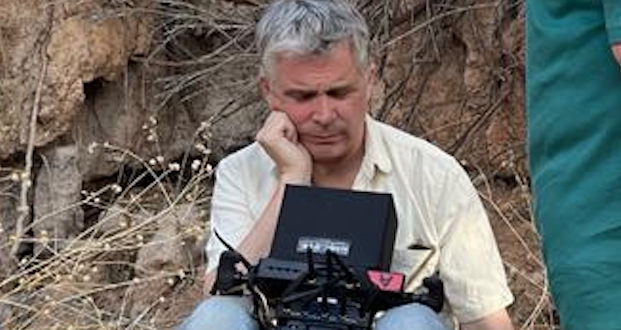

Corky Lee, the legendary Asian American photographer who chronicled half a century of activism, joy, and resistance, became more than a documentarian—he was a movement unto himself. Since his death in 2021, his legacy has been honored everywhere from The New York Times to PBS NewsHour, American Masters and most recently in the poignant documentary, Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story. But who was the man behind the lens—the relentless, mischievous, deeply principled artist who reshaped how America saw its own margins? Filmmaker Jennifer Takaki spent years shadowing Lee, capturing his process, his wit, and his unyielding mission. In this interview, she reveals how she came to know him, why his work still reverberates, and how a planned five-minute profile turned into a journey that lasted almost 20 years.

Jennifer, when you met Corky at the Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) chapter meeting, how did you know you wanted to make him the feature of your next documentary?

JT: I didn’t want to, or plan to, do a documentary on him. I had decided prior to meeting Corky that I was going to do five-minute vignettes on people who were singular-vision type people. And I also didn’t want to research the person. I would find them organically and shoot them organically, as I found out about their story.

What made him stand out and motivate you to feature his story?

JT: He’s just immediately interesting. The reason we even met was, the event had ended and, I asked the closest person where the bathroom was and it happened to be Corky Lee. He said he didn’t know where the women’s room was, but he knew where the men’s room was. I said, “Just tell me where the men’s is, and I’ll find the women’s.”

He said, “Actually, the history of the building is…and it was built In blah, blah, blah. And, it used to be an all-boys school, so the women’s room could be on a different floor.” And I just said, “Just tell me where the men’s room is!” He’s like, “’l’ll show you!” And I was like, “Who are you?” “I’m Corky Lee!” and then he started to tell me about all these things that he did. He’s such an immediately likeable person and I loved his history-driven stories. And how random things are that you could find this person that cared so much about AAPI [Asian-American Pacific Islander] history. And I really frankly couldn’t figure him out, so I knew immediately that he would be a subject that I would start to film in for my five-minute vignettes.

What building was it?

JT: Everyone asks me that. I don’t recall. But one of my last interviews, I think we sorted it out that it might be CUNY, John Jay, the criminal justice building. I didn’t even remember the building. I really did intend to do a five-minute vignette; I didn’t want to do a documentary. Corky was already known in the community. I’d never heard of him before, but I knew that for me, I just wanted to do a five-minute vignette and just tell people who this person was – but when it was finished I felt like it was not finished (laughs), so I kept shooting.

So you were in the moment of wanting ideas for five-minute vignettes?JT: The idea was New York is a great city to meet random people and there’s so many people that are so interesting and for whatever reason I felt that single-vision people were the type of people I wanted to film.

Did you end up making it?

JT: Yeah, but I didn’t show it anywhere.

So then you decided to do a long-form documentary on Corky?

JT: I didn’t decide to do a long-form until 10 to 12 years later. I’m a huge commitment-phobe and honestly it was just a lot of pressure. You don’t go in doing a documentary about somebody like Corky, someone so beloved and entrenched in a community, someone who’s so historical – you don’t go to Corky and just say, “I’m going to start shooting you,” you usually have a plan. Honestly, I really just wanted to organically find out who he was. So, I just started following him around, and he didn’t ask when it would be finished, and I didn’t answer when it would be finished. We just were. (laughs) He shot and I shot him.

How many years did you film him for the documentary?

JT: It was off and on for 19 years; from 2003 forward. We finished the film in-time to have our world premiere at Doc NYC in November of 2022.

He had passed by then.

JT: He had passed by then, but he did see a couple of rough cuts. I was interviewing others about their story, it wasn’t just Corky’s. It was very important for me to talk about the broader history of the Asian. Corky was one of many people [who were] part of that history, but he was really that string that brought everyone together. And what also differentiated him is that he started in the ‘70s and never stopped, while many of the activists became professional doctors, lawyers, and Corky stayed within the community and kept shooting.

So you didn’t tell him you were officially doing a long-form documentary, how did you know when to go with him? Would he just call you every time he goes out?

JT: No, Corky was usually really good about staying in-touch. Sometimes he’d write these long emails or text messages about “on Monday I’m doing this and this and this,” and I would see what would fit into my schedule. Sometimes we would talk, sometimes when I saw him, I would know the next event; it was very organic. I think that that’s what made it work, was that there was no pressure on either of us to have to perform, and we were just good about saying, “I’ll be there.” Honestly, Corky was so together, so on, so ready, so available, so in-the-moment all the time, that you could be having coffee with him and he would say something interesting and if you wanted to, you could put up your camera immediately and start filming what he was saying, because he was just that guy. He really never stopped me from filming, never said “No,” never said, “This was not a good topic.” He really just talked. He was very open.

I am guessing the filming ended because he passed. Is that officially when it ended?

JT: I had rough cuts. The way that I structured this idea about filming him was, that when I shot the 2014 Transcontinental Railway, for me, that was always the end of the film. And I have to mention Linda Hattendorf, my editor, came on board initially in 2012 when I raised some money to do a promo and she came on board officially in 2015. She really was, in my opinion, the second most important person on this film, outside of Corky. She really understood what I wanted to do. She has the heart and soul of an activist and she really had so much admiration for Corky and what he stood for. She was the filmmaker of “Cats of Mirikitani” about a Japanese-American homeless painter named Jimmy Mirikitani; when I saw that film, I knew I wanted her to edit mine. Linda is amazing and brilliant. So we always wanted 2014 to be the end. But we also had another end, which was the Asian-American movement reunion. There were just many different endings, but the pivotal ending was always meant to be 2014. But after that, I kept shooting. He was hard not to shoot, that’s the problem. He was just on the go all the time. He was an incredible soul.

Did you have another job?

JT: Oh I had many jobs throughout this, I was not getting paid to do this, in fact I had to pay to get this done. That’s partly, I think, why it took so long. In any filmmaker’s world, the money is always the hardest thing to get. So, on top of, while you’re filming, you’re supposed to be applying for grants and thinking about your distribution. It’s quite a feat that any film gets made and I think everyone should appreciate all films because it is a lot to do.

It was funny you said you’re commitment phobic, but you’re a documentary maker, so how do you get around that?

JT: Well, I wasn’t a documentary filmmaker until I started doing this film. I would do family documentaries but it had a beginning, middle and end.

What were you doing before you made this film?

JT: I’m a big proponent of family history and people would hire me and I called them “family documentaries”. I would do interviews with people, edit it and put their histories together. But it’s different and I’m talking about their past and their ancestors and what brought them here; to give the family a sense of who they were, is so important. So, that’s what I did. I didn’t call myself a documentary filmmaker back then. I just did documentaries on people. (laughs) The end-all be-all has never been to necessarily be a documentary filmmaker. It’s to tell the story in whatever format that is.

I’m glad you did show he had a wife and a life outside of this lifelong passion of photography. I didn’t recall he had a wife, when I met him years ago.

JT: Yeah most people don’t. And people who knew him for 40, 50 years, just found out through the film. So he’s still a mystery to many. He could compartmentalize like no one else could.

There was the scene out West where Corky wanted to reenact the Transcontinental Railroad photo of 1869 and include Chinese immigrants who were not originally recognized. Was that organized via worth of mouth or social networks? Were those people descendants of the railroad builders?

JT: Some of them were descendants. So, Corky wasn’t just a photographer; his base was as a community organizer. He started as a community organizer and then he learned how to use photography as a way to make social change happen. So that all happened kind of simultaneously in the early ‘70s and would get him on his trajectory. He would often have these amazing ideas and he would get people involved in them. For the railroad, he really was the person spearheading, and getting organizations in Utah, and he organized the buses, and got people on the buses. When Corky talks about something, people really do step in to see what’s going and to hopefully show up and help. Corky was often in the middle of, not only just at the end of, taking the pivotal photo, but often, spearheading the whole event itself.

Was that photo showed anywhere?

JT: Apparently it’s at Promontory Summit. It’s in a lot of places. People have it in their personal archives. And Corky always knew that that that would become one of his pivotal photos.

He makes a comment that studio rental for the darkroom used to be pennies. So did he ever switch to digital SLR cameras, or did he always shoot with film?

JT: He did both. In 2002, he started carrying both and I think he talks about that, maybe in the scene where he’s developing photos, where he carries a digital as well as a black and white camera – Corky, being Corky. One camera is pretty heavy (laughs); think of two cameras with lenses!

How did he make ends meet when the printing shop closed?

JT: He was receiving benefits, I think social security benefits, and his wife had passed so I think he had some money from that. He was making ends meet. I felt like Corky was always just getting by.

What was the path to airing the film on PBS? Was that always the destination?

JT: Any filmmaker would probably say it’s not easy. And it wasn’t easy. We had Don Young from Center for Asian American Media come on board, and he really helped steer us and helped get us onto PBS. Without him, I don’t think we would have.

They probably all knew Corky, I would assume.

JT: Yeah, the struggle has always been, and I still feel it, despite the fact Corky has a google doodle, despite the fact he has a book, despite the fact he has a feature film, I feel like he’s always under the radar. It was really hard just to get money; I didn’t get grant money before he died. I feel like a lot of people knew who he was and I always felt like he flew under the radar. I think it was really tough getting on PBS in the sense that people thought Corky was too New York before he died. Before he died, I think even those within the AANHPI [Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander] community who knew wanted their story to be told. So if you knew Corky, say from L.A., if Corky was still alive, you might say, “Corky was in L.A., why don’t you put stuff in there about L.A.?” Or Philly, or Denver, wherever everyone lives. And I always felt people wanted to see their side of the story that’s about Corky, and that Corky was too New York for people. But when he died, that is when everyone started to see the larger picture of Corky and the bigger impact he had. I wanted to create a platform for people to learn about what Corky did and why he did it so that he would be able to get to middle America and everywhere else and to be able to talk about his photos after screening the film. Well, of course, that didn’t happen quite that way. But then I also really believe Corky will become as iconic as Bruce Lee, or Muhammad Ali. People who are really iconic, really bring together people and have a sense of belonging and really have a strong sense of self and history. And I think that’s why I feel like Corky is still falling under the radar, but not in a bad way. I really do think that this momentum is moving forward now. The whole premise of even our impact campaign was to make Corky not just a local New York hero, but a national icon. And I think that that has, and is, changing.

When he passed, I was surprised at how much of what you call an “icon” he became, in all the decades since I first met him. Then I saw his New York Times obituary.

JT: Think about even post-death, all of these national magazines are recognizing Corky and yet he’s still considered a local hero. He’s still kind of clumped into a local story, when he is much more of a nationwide, if not global icon. There’s something that he just continues to fly under the radar a little. It is what it is. (laughs) I thought that he was doing really important work and I really wanted to provide a platform for his work to get out there, and for people to know who he was.

He was incredibly charming and funny and so informative. He’s such a great person in a crowd, he could talk to anyone, any age, he could really inspire people of all ages. And I just really felt that that was such an important story; to have him tell these stories. People listen to him because he just has so much to say and he’s so knowledgeable, not just about Asian Americans, but American history in general. And I think that, that is such an important part of who he was and his messaging.

When Corky passed, I was surprised he became such a legend; I had known him decades ago working at the printing shop. I guess he didn’t quit what he was always focused on doing.

JT: He never stopped, he never stopped. Daily, he never stopped. Daily, he was always shooting; he was always on. Corky could be passing-by something and shoot it. He just would see things or he would find something interesting as he walks. It doesn’t have to always be an event. A sample of that is the sewing machine scene; that was just Corky seeing sewing machines in middle of the street and he has a whole story of why they’re there, and he takes a photo. And then, that becomes the story of telling that history of the demise of the garment industry in Chinatown.

Did he always have a place to showcase?

JT: No. (laughs) Who does that? Who takes photos and doesn’t have a place, or is not paid for them? (It should be noted that Corky did this at a time prior to iPhones so it wasn’t at all common) I couldn’t figure him out for the longest time, why he was doing what he did. But he knew that the photos would last a lot longer than he would be around. He wanted to be able to tell that story and to have the photos left so that other people could tell stories. You’re a writer, you need images for your story; that’s what Corky had in mind.

Who has his images now?

JT: It’s with the Lee estate, out of everyone in the family that was in the film, only John Lee is alive. He’s the second youngest brother and he’s the head of the estate. They have a book out called “Corky Lee’s Asian America.”

What is your average day like now?

JT: I don’t have an average day anymore. It’s been so full-on with the film. There’s been so much traveling, and so much preparation for all of the travel. We did a theatrical release, we just did PBS, and there’s a lot that goes with that. Every screening we have a panel. We had a sold out show in New York. We had a talkback recently for Photographic Justice to lead into the last week of PBS. And today I’m sending out all the packages – we gave away swag. So, there’s nothing that’s normal.

You should definitely submit it for the Oscars.

JT: It’s too late. Awards aren’t important to me. For me, it really is just getting it out into the community. I get that awards help with that recognition. If you go for an Oscar [nomination], you need at least $1 million minimum and you have to have three screenings a day. It’s a big campaign, a lot of money. I would rather put the time and energy into educational and community screenings, which is what we’re doing now.

Did Corky have any L.A. connection or do any photography in L.A.?

JT: Corky was everywhere, if he took a trip somewhere, he took his camera. He was always meeting with people, he had a lot of friends all over the U.S. In L.A., I think he did a UCLA fellowship. Corky was in Boston, Philly, so many people could claim Corky was part of their own history because he very much was. But that was not the focus of the film, it really was just showing who he was in a New York-sense, and being part of the Asian movement on the East Coast.

Anything we haven’t mentioned that you would like to add?

JT: I guess one of them would be to inspire the young generation to understand their history and the role models who helped pave the way. Obviously, this isn’t the end-all be-all of role models, but there’s a very long history of Asian Americans in the United States and we all have a stake in it. I think it’s important to not only show that history but to pay homage to those in the community who have been working along the way. I also think family history is such an important part of it. I’m a big fan of people documenting their own family histories, but also just being kind and supporting your local organizers that are in your community. Every community has people like Corky. Not to the extent, Corky really is exceptional in so many ways, but you have local people doing good in the community and sometimes they need help and support and you just need to find those people and do what you can. A lot of them are unsung heroes like Corky.

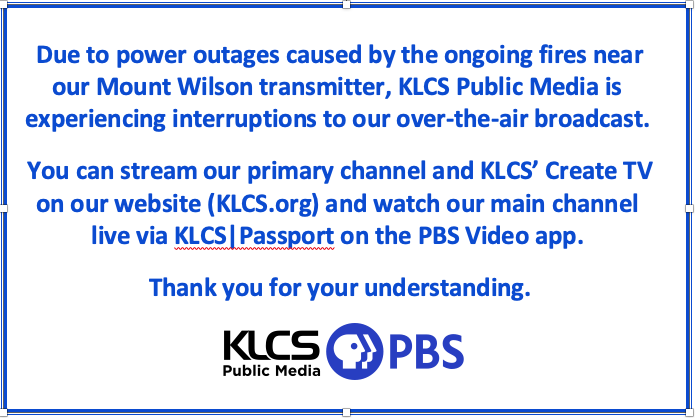

About PBS…

JT: It’s such an honor and privilege to be on PBS. It was so important for our film, it was the perfect fit for our film, we really, really wanted to be on PBS. I know Corky would have been so happy and also the national broadcast aspect of it was really, really important. To know people outside of the major cities are able to learn about Corky is so important to us. So we’re very thankful and appreciative to everyone who made that happen. It was a very quick process, we found out at a very late stage and everyone on the PBS team worked with us steadfastly. There were so many people at PBS who I really wanted to thank. Special shout out to Wendy who I believe was the main person at PBS that really supported us to get a broadcast. And then there was a whole team of people who made that happen including Emily, Kelsey, Cara and Dan. We were picked up very late and everyone really worked with us, on a very tight deadline, to get us on air!

I just want to say PBS was a huge endeavor it’s not the end endeavor. It’s not like, “Ok, now we’re just going to rest on our laurels and that’s it.” But it was a magnificent one to achieve for sure.

The Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) should honor him with a lifetime achievement, because he wore their sweatshirt much of the time in that documentary.

JT: Oh yeah, he wore that a lot!

Maybe that’s why he was in so many obituaries, because so many journalists knew him.

JT: He was in everything; I think it’s a combination. I think there were a lot of people in the media community who knew Corky, appreciated him and wanted to get his story out. So, they definitely would have made sure the stories got told. But, I think, also the recognition of who Corky was and the loss to this community. People are still reeling, to this day, with the loss. Corky was very respected and very appreciated, but he was also invisible and so present and I think we all assumed that he’d be there. I always felt that, frankly, Corky would be living longer than I would. (laughs) He just was always around and always great. It is really sad.

[This interview has been edited for length and clarity.]

Tune-in to watch Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story, Sunday, May 18th at 7PM. Members can stream the documentary film on-demand via KLCS|Passport.

And visit the show’s official website to learn more about Corky, his life, and his work.