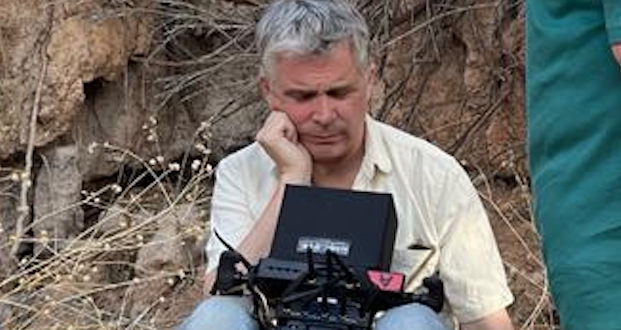

Set off on an extraordinary journey with Massachusetts Institute of Technology [MIT] Professor Alan Lightman as he navigates the depths of human connection and the pursuit of life’s significance in Searching: Our Quest for Meaning in the Age of Science. In this captivating series, spanning three thought-provoking episodes, Lightman delves into life’s most profound questions. Inspired by a moment of serenity and a sense of unity with the celestial universe, lying on a boat off the coast of Maine,

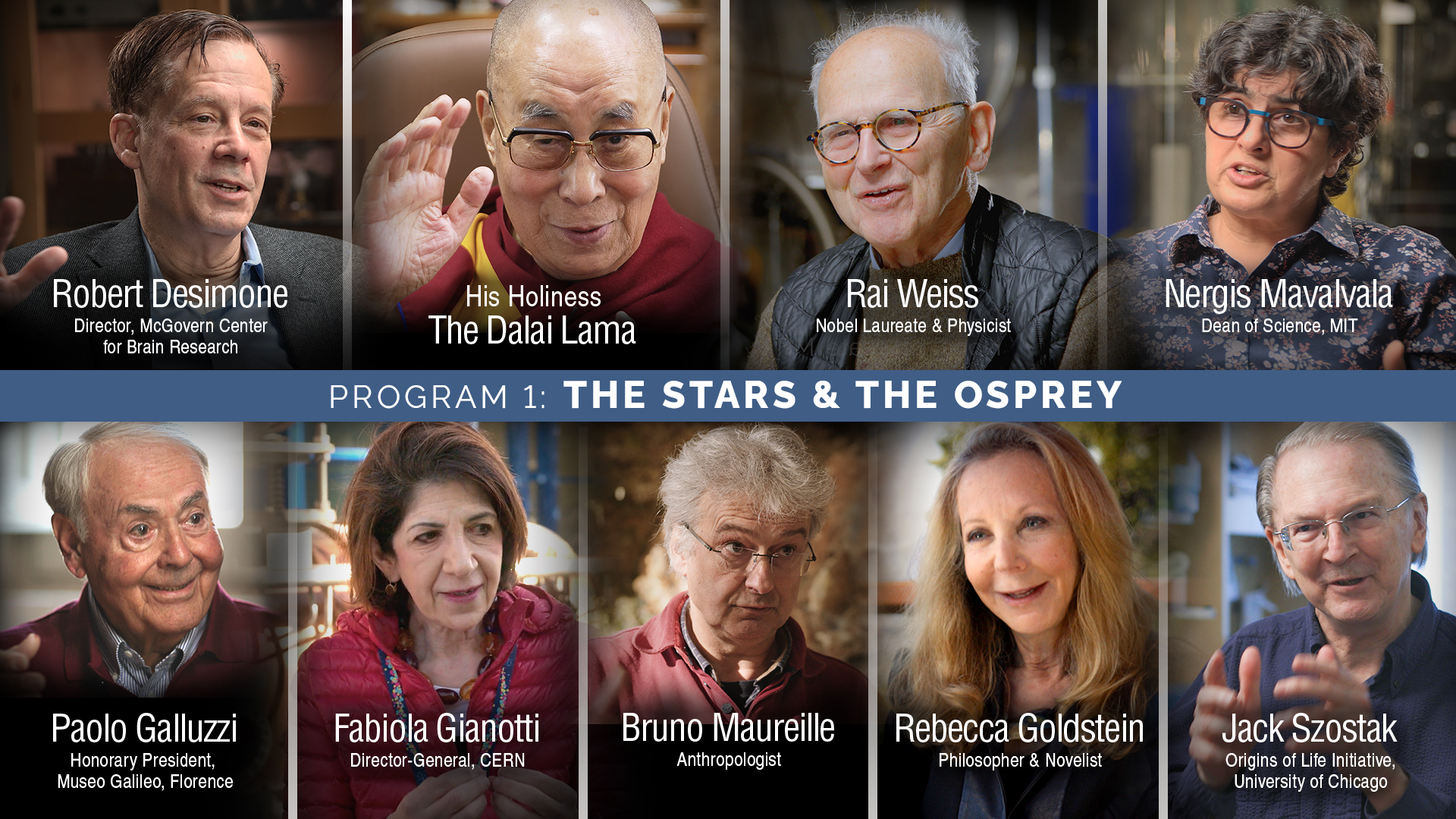

Lightman penned the book that serves as the show’s foundation. We spoke with Dr. Lightman about the learning and discoveries he made through the course of this scientific odyssey, exploring his encounters with fellow luminaries and the genesis of the show’s concept. Executive produced by Geoff Haines-Stiles, known for his work on Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, “Searching” promises unparalleled insight, from holding Galileo’s telescope to experiencing Albert Einstein’s Swiss abode. Join us as we delve into the extraordinary with Professor Lightman.

Professor Lightman how did this show come about? Was it based on your book?

Yes. The start of this was about five years ago, whenever my book “Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine” came out, I got an email from Geoff Haines-Stiles. Geoff said that he had read my book and would I be interested in working with him on a documentary based on the book. I wrote back and said I would be interested if the documentary explored the philosophical and theological implications of science, as well as the science itself; which is what the book does. I didn’t want to work on just a science program. He agreed with that, and then we got together the summer of 2020. He visited me and we talked further about it; it was also with his partner Erna Akuginow. The first thing we needed to do was to get funding for this series. And we made a proposal and eventually the Templeton Foundation, which is based in Philadelphia, gave us funding. We had a meeting somewhere around the fall of 2020 and mapped out what we thought would be the content of the series.

I started watching the show in the middle of an episode, the camera zooms out of a house on an island in the middle of what looks like a lake, and I thought, “Does he really live on an island in the middle of a lake?” You obviously do.

It’s in the ocean, it’s off the coast of Maine and my wife, who is a painter, and I have been going there for 30 years in the summer time. We spend the entire summer there, we’re not there during the winter. A lot of the filming was done on the island. But as you saw in the series, the filming was all over the world.

Seeing that you live on an island intrigued me, do you get a lot of people talking to you about that choice? If so, what is your answer? I’m assuming it’s about being immersed in nature.

Yes, it’s being disconnected from the wired world. It’s a place of quiet and solitude, it’s a place where I can think and write and my wife can paint, so we’ve always considered it to be our spiritual center.

The series showcases some of your colleagues like Ray Weiss, who I’m sure is a legend among scientists, and you highlight research that often is not widely known. Is bringing Dr. Weiss to TV in a popular science show, a continuation of what Carl Sagan did? Perhaps going further and in a different direction, like you said?

Of course in the series, I talked to many scientists besides Ray Weiss; I talk to Nobel Prize winner Jack Szostak. I think you can view the series was continuing what Sagan did in a certain way, in that we’re trying to help the public understand science, but I’ve never thought of myself as being a disciple of Sagan, I have been uniquely interested in the philosophical, ethical and theological implications of science. That has been my thrust, I’ve written many books on those subjects and although I greatly admire Carl Sagan, and of course Neil Degrasse Tyson did a series, it was actually called Cosmos. Neil DeGrasse Tyson would be much more of a disciple of Sagan than me. Even though I have much respect for Sagan, I’ve gone in a different direction. All of us – Sagan, Tyson, and I are all interested in bringing science to the public, but I have other interests in addition to that.

You said your journey started with you on a boat in the middle of the ocean and feeling connected to the stars. I had a related experience, standing against the wall of the Campanile at Cal Berkeley and feeling like I was floating in the stars. Do you get frequent feedback that it’s a shared experience?

It’s a very common experience. Maybe not that precise, but many people have written to me about similar experiences where they felt connected to the cosmos in various ways. You can be connected to the cosmos by watching a sunset, or watching a baby being born. There are various ways, but that feeling of being part of something larger than yourself ,I think many of us have had that feeling.

Quantum physics seems like the branch of physics that allows for a spiritual or metaphysical element to be introduced. There appears to be breadth to imagine what the mind cannot make sense of, in contrast to other, more-structured science disciplines.

What about the Big Bang in cosmology? Doesn’t that also connect physics to theology or spirituality? I agree with you that quantum physics is a connection, but I think there are other connections as well.

Other places where physics bumps its shoulder against spirituality, theology.

Did you become a scientist because you were trying to find the meaning of life?

When I was a child, I was interested in a lot of things. I was interested in science, I was interested in the arts; I wrote poetry. Some of my poems were definitely about trying to find the meaning of life, whatever a 12-year-old could do in that department. So I’ve always had an interest in science and the arts. And when I was college, I majored in physics, but minored in philosophy, so I’ve always had a philosophical bent.

Did you see each episode as a journey of what you wanted to share with us?

Yeah. I think so.

Was the book a template for each scene in the show; did you go to the caves in France to look at the ancient drawings?

It’s a good question. Yes the caves in France were in the book, but there were scenes and conversations in the television series that were not in the book. I don’t think that Geoff and I felt like we were slaves to the book. There were a lot of things in the book that were in the series, and a lot of things that weren’t. We did envision the series, in addition to being for a general audience, we thought of it in terms of its educational potential. It’s actually been used in a high school and several colleges and the website that accompanies the series has a lot of educational material in it, that we think that high school and college students would use.

I saw that you and Geoff co-wrote the script, did you make the script your guide for how you would shoot each episode?

One thing I learned from Geoff and Erna is the way that a cinematographer looks at a narrative. And they think about the narrative not only as the script, but the scenes, the visual aspect. I learned that there’s a whole story being told by visuals. When Geoff shot the series, he hired about six or eight different camera crews around the world. He shot it movie quality, I think they call it 4K. When Geoff and I would work on the script, he always had in mind the visuals to go with it. Sometimes we would write some sentences and he would say, “We don’t have any visuals to go with that.”

So he was always thinking in the visual dimension; it was a lot more than just sitting down and writing words for a script. This was a new experience for me. I’m used to writing books and when you write books you hope that the words alone can stimulate the imagination of the reader and that your reader can visualize things, but with television and film, you actually have the image there in front of the viewer. So a person like Geoff, a filmmaker, he’s thinking about those images all the time.

Episode Three is called “Homo Techno,” you bring up the fact that we’re becoming robot-like in some way. I agree that too often we’re preoccupied with a piece of glass in our hands, instead of being present and engaging with the world around us. I interviewed this man who was paralyzed from the neck down; I think we certainly are becoming part human and part machine and I think that at some time in the future, we’ll probably have chips implanted in our brains that connect us directly to the Internet. And that’s sort of what we mean by the expression “homo techno,” which was a chapter in the book.

As your first time doing a TV show, what was it like? Did you find it easy, what did you learn from the experience?

Well, it was not easy (laughs). One of the first things that I experienced is that I was working with a group of people instead of being a solo artist. When you’re a writer, you’re usually sitting in a room by yourself, you’re doing a solo act. Whereas a film crew is an orchestra. There were lots of talented people around me, starting with Geoff. We had a wonderful musician, Zoey Keating, who not only composed, but performed all of the music. We had all of these very talented camera people. Almost every time that Geoff and I would go to shoot a scene, there would be like 8 people there that were all involved. We had three cameras on each interview, from 3 different directions. One on me, one on the person I was talking to, and one camera on the two of us. Something that I learned was the importance of the visual story. Ever since making this series, when I see television or movies, I’m seeing it with new eyes. I’m thinking about where’s the camera now and why did the cinematographer decide to shoot that scene. And I’m looking at every screen image as a painting, that’s what Geoff does. Every frame is a painting.

I love that you asked the scientists you interviewed, that if they could hit a button to get the answer they were seeking, would they do it? I think their answers show their raison d’etre; why they are motivated to be scientists. Were you surprised by some of their answers?

I think I knew that there would be answers on both sides of the question, but I think that mystery is one of the drivers of science, and I think it’s one of the drivers of the artistic and the scientific imagination. And if we had all the answers, I’m giving you my own response to the push the button question, if all of the mystery of our endeavors was taken out of it, it wouldn’t be the same creative impulse.

That’s really interesting. You wouldn’t think of scientific endeavors as creative, but in a way that is their creativity.

That is. Oh, I think scientists are very creative. And the greatest scientists are extremely creative. It’s just another form of creativity.

I was talking someone whose husband works in Information Technology, but he is a natural jazz musician, and we were saying it’s the same brain, seems a lot of scientist are musicians.

Yeah, that’s true. Einstein played the violin and Heisenberg played the piano. You can mention lots of examples of that.

Do you think that if we were all a little more science-minded, we would be more considerate of the environment and maybe less prone to wars, or be kinder to each other, because we would realize that we are all connected?

I think that closer contact with nature does make us more appreciative of earth and of nature. I think there’s another kind of appreciation that’s broadened by astronomy in particular. Especially in the last 20 years, when we’ve been able to observe lots and lots of other planets, not just in our solar system, but much further away than our solar system. And we’ve found that most of them have very inhospitable conditions. They don’t have atmospheres of oxygen, they have sulfuric acid. They have very rough, inhospitable environments and what that makes you appreciate is that an environment that’s congenial to life is not ordained, it’s not a necessity, it’s very rare and it’s fragile. And our planet could turn into one of these inhospitable planets if we’re not careful. So that’s a respect for nature and an appreciation of nature and a desire to protect our particular environment that’s emphasized by astronomy. People have done studies to show that the exposure to nature is actually good for your health. It’s good for you physical health, it’s good for your mental health. And one of the unfortunate consequences of our wired world, in which we’re all looking at our cell phones all the time when we’re walking in the woods instead of taking time to appreciate where we are, is that we have distanced ourselves from nature. We’ve used technology to be a layer in between us and nature. That’s one of the down sides of modern technology; it has created further distance between us and nature. And, I’m sure that we’re suffering both physically and mentally from that.

I loved that you showed us Galileo’s telescope; I was not aware that there was a museum in Florence, Italy, housing his personal items. Was that part of the book, and if not, was that the first time you got to engage with that telescope? What was that like?

Galileo and his work was in the book, but of course it was an incredible thrill to see his original telescope from a few feet away. I got to actually hold an exact replica of his telescope and that was pretty thrilling. It was also thrilling to get to talk to the Dalai Lama. There were a lot of thrilling moments for me.

I love how the episodes are sequenced, and to see a place that we might not think to visit. Had you been to Einstein’s apartment before?

No, I’d never been to Einstein’s apartment before and was really delighted that I was able to go there. It was actually Geoff’s idea because we did a scene at the top of the mountain in Jungfraujoch in Switzerland, it was the final scene of the final episode. It was brutally cold there, but we were not too far from Einstein’s house and Geoff decided, “Well, since we’re that close we ought to go to Einstein’s apartment!” and we shot a scene there as well. That was certainly a thrill to be able to put my hand on a piece of furniture that he had touched himself. That was pretty amazing.

Did you get a feeling or a sense of him being there?

I got a sense, yeah. Some of his atoms and molecules were still in there, in that apartment. And when I put my hand down on a table that he worked at, I was almost certainly touching some of his atoms and molecules, which was pretty amazing. So it was definitely a feeling of being closely connected to him.

Some people, in other disciplines, would think of that as his imprint of energy.

I’m a materialist, so I think of it in terms of his atoms and molecules (laughs).

Your way of seeing science can, in a way, help the metaphysical folks have more gravitas; they could adopt your theory.

It’s a bridge between that group of people and hard-nosed scientists. I actually have a name for myself, I call myself a spiritual materialist. I’m a materialist because I believe that everything is made out of atoms and molecules and there are no supernatural essences or anything like that. But I do have these spiritual experiences, like lying in the boat, looking up at the stars and feeling part of them, or feeling connected to things larger than myself, appreciating the beauty of nature, all of that is my version of spirituality and I don’t think that is incompatible with science in the slightest.

Do you have a favorite scene of the show or experience? And did you learn anything from doing this show yourself?

There is a favorite scene, I’m not in the scene, but there’s a scene – we’re in France and there’s a river there and there was a mist hanging over the river and Geoff saw that and decided that was a beautiful scene. He got a drone to fly about 100 feet over the river following down the course of the river, and it’s just an absolutely breathtaking scene, so I think that that’s my favorite scene in the whole series.

Did you learn anything new from the show?

I learned a lot. I learned a little bit about how film makers work. We had some pretty long days, we had some days that were probably 12 hours. I learned what it was like to work with a group of talented people, to be part of a symphony orchestra instead of a solo artist. I think of some of the conversations I had, all of the people that I talked to were very interesting and I learned little bits here and there from what people said. I learned from the Dalai Lama, I learned from the philosopher Rebecca Goldstein; I learned a lot from the biologist Jack Szostak about the challenges in trying to create life from scratch in his laboratory. The whole things was a learning experience for me.

What is your average day like now?

I do a small amount of teaching at MIT, so a couple days a-week I’ll go [to the campus]; I supervise a thesis at MIT, I’ll spend some time on that. I spend most of the day writing but I also spend a fair amount of time on a nonprofit association that I started in Southeast Asia called Harpswell. The mission of that organization is to help empower young women who work in Southeast Asia, and I go there once or twice a year. So, I spend part of my day with that, and I also have children and grandchildren. The first three things I mentioned – I work on those every day. I go jogging first thing in the morning. That’s a constant part of my day – exercise. And then once every month or two I’ll go with my wife to visit our grandchildren.

Besides the sciences, you found a passion that motivated you enough to create a nonprofit. It does not seem a likely direction that your work would go.

Not likely, I went on a vacation just almost 20 years ago, and met a very inspiring Cambodian woman who inspired me to start this nonprofit organization to help empower women. It’s a very unlikely new direction for my life. My work in either physics or writing would not normally have led to that path. So, it was an accident, but a lot of accidents happen in life and many of them are good accidents. I think that the importance and impact of accidents is much underrated.

MIT has such a rich student culture, do you feel as faculty you missed out when you see how much fun they have? Do you wish you had gone there?

No, I’m glad I didn’t go there. I applied to MIT and got in and I have great respect for MIT but I decided that I wanted a university that was as strong in the liberal arts and the humanities as it was in science, and that’s why I didn’t go. But MIT does have very good humanities now, it didn’t so much when I was applying for college years ago.

What’s next for you and what’s next for the show? Is there another episode, or would you like to do other topics that are not in your book?

What’s next for the show is Geoff and I are now working on educational outreach. We’ve developed this series, we’ve got this great website that we’ve developed all kinds of great educational materials on it and we’re now working on trying to introduce the website and the series to high school and colleges. In terms of my own work, I’m working on a couple new books and I’m always writing something.

There’s not going to be another season?

We don’t plan for that at the moment.

Standing in the last shot, you can tell you were really cold, what was that like? The last scene, the last shot. That was a beautiful scene. Had you been there before?

No, I hadn’t been there. It was gorgeous, it was a beautiful setting with the Swiss alps on both sides of you. My lips were so cold I could barely get my mouth to move, Geoff and I at one point we were thinking, because my voice didn’t come out very well, we were thinking of editing-in carefully lip-synced voiceover over. And we finally decided why not just let the viewers see how cold I am, and hear how cold I am. Even though my voice was muffled, you could kind of understand what I was saying. We though, “ Let’s let the viewer experience the cold,” so we decided against dubbing my voice. Some of the camera crew got altitude sickness, we went up to the mountaintop the night before and I think it was like at 12,000 feet. I took altitude sickness pills, but some of the camera crew forgot to take the pills and they were sick the next morning. It was a thrill to work with Geoff and Erna who are such professionals. As you mentioned earlier, Geoff was one of the senior producers of Carl Sagan’s Cosmos. He’s had lots of experience and it was just a thrill to work with a master.

Anything you’d like to add that I haven’t asked?

I don’t think so, you’ve asked a lot of good questions. The website that we have is in both English and Spanish and it has subtitles for people who have trouble hearing. You can watch the series on the website, you can also take advantage of some of the backstories of the series and some of the educational material. All of that is on the website. And it will be available to be streamed on PBS.org as well. That’s still possible for people who are not able to catch it on television, you can stream.

All photos, credit: Searching: Our Quest for Meaning in the Age of Science

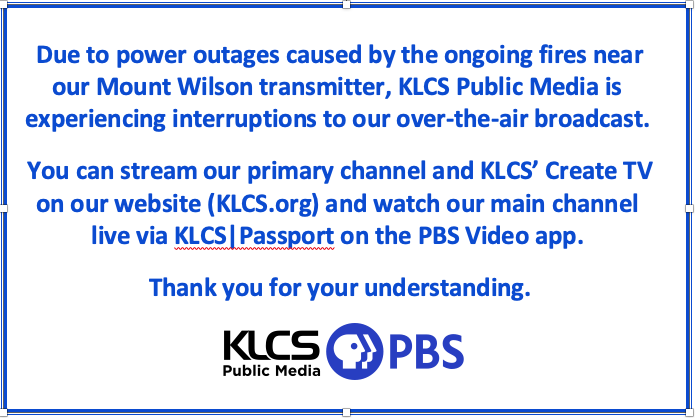

KLCS will rebroadcast Searching: Our Quest for Meaning in the Age of Science starting Tuesday, April 2, 2024 at 9:00 PM; check klcs.org/schedule for the full broadcast schedule. The complete series as well the resources mentioned in the interview can also be accessed via the show’s website: searchingformeaning.org.