She was a trailblazing virtuoso, a barrier-breaking star, and a fierce advocate for Black artists—yet Hazel Scott’s name was nearly erased from history. The Disappearance of Miss Scott, the captivating PBS documentary (now streaming on KLCS|Passport), resurrects the extraordinary story of the jazz pianist and singer who became the first Black person to host a national television show, only to be silenced by the McCarthy-era blacklist. From commanding Hollywood’s attention to leading on-set strikes, Scott’s brilliance was undeniable—yet her legacy faded, save for fleeting homages like Alicia Keys’ dazzling dual-piano tribute at the 2018 Grammys.

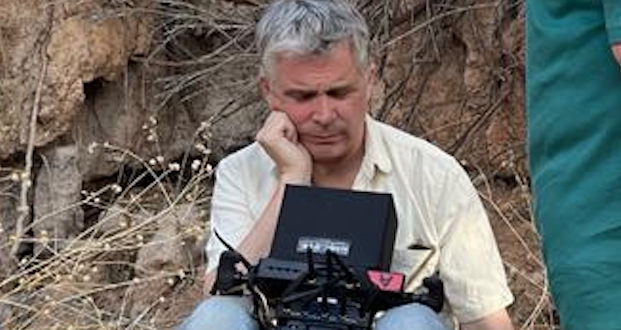

Helmed by acclaimed former network correspondent Sheila MacVicar, this film is both a revelation and a reckoning. In an exclusive interview with KLCS from her Paris home, MacVicar reveals how she uncovered Scott’s story, the profound lessons of her life, and her own journey beyond the news desk.

Sheila how did this project come about?

SM: I’ve known Adam Powell III who is the son of Hazel Scott and Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., the Congressional Representative from Harlem, for a very, very long time. And over a long number of years, and various places, a lot of dinners, I’d heard stories about his family. I knew a lot about his father, of course, and I knew that his mother was an entertainer and I hadn’t really clocked just how extraordinary her talents were. And then I saw something he put on Facebook on the occasion of what would’ve been his mother’s 99th birthday. It was a beautiful picture of his mother seated at a grand piano. I looked at it and I thought, “Huh, that’s really interesting.” And so I started to read, and I read some more, and I called Adam up and said, “Um, has anyone ever made a documentary about your mother?” And he said, “No.” And at that point he was still in the possession of his mother’s personal archive, which is now in the Library of Congress and we did a deal with Adam for access to that archive, which included an 800-page unpublished memoir that she had been writing in the last years of her life. And Adam talks about [the memoire] in the film, he says, after she died, they found in her apartment just reams and reams of yellow legal pads; that was the basis for this memoir. We got access to that material, we digitized it all, we gave it to the Library of Congress where it now is, and that was how our project began.

The voice-over by Sheryl Lee Ralph – was that script all from Hazel’s legal pads?

SM: That was all from her memoir. Those are Hazel’s words as she wrote them. And obviously, we didn’t have her voice saying those things. We thought they were important to the story and that they reflected what Hazel really thought and what she was writing about. And it was important to have that voice.

Author Karen Chilton is featured in the documentary; was that form the same book she wrote?

SM: Karen’s book is totally separate. We conducted all our own research; we did use her book. And from our possession of the memoir, is how we came to all those quotes.

Was Hazel’s memoir ever published?

SM: No. No, as a matter of fact when Adam and his then-wife discovered it, it was all loosely scrawled handwriting on these legal pads; she and Adam actually transcribed it. She may have started transcribing it before Hazel died, and it was those pages that we found in these bing plastic bins.

What, do you feel, is the take-away of Miss Scott’s life story?

SM: Hazel is so many things. She is a virtuoso, she is a brilliant pianist, she’s a brilliant jazz artist, she was a stunning Hollywood star, but most of all – she is true to herself. She’s true to her values. She’s true to her own North Star, even when it cost her; and she knew it would cost her. The perfect example of that is the strike that she led in Hollywood. Harry Cohn was notorious. And if you crossed him, you were dead. And she knew that. She had a good enough relationship with Cohn before the strike that she would have gone to him and say, “Listen,” which she later acknowledged in her memoir was probably a tactical mistake, that she did not go to him and say, “Listen, black actresses are not being treating well.” And instead she just stood her ground on the set. And of course there were other voices that did the talking. And the talking said, “Hazel Scott is holding up production.” And we all know how lethal those words are.

She was the first black person to have her own TV show, and though the documentary we learn that the network tried to destroy the footage; did any of it make it into the film?

SM: No. Her show has forgotten for a long time. There’s a common misunderstanding that her show existed only for the summer of 1950, that’s no true. We found documentary evidence that the show had begun in February 1950 and that it had begun as a local show in New York on the local DuMont channel; it was very successful. It expanded, it became a national show, and then it became a multi-day a-week event. I think three days a week, nationally. And in those days, this is the pre-satellite era, how did they move the material from one station to the next? They created what were called Kinescopes. Kinescopes were very crude – basically you were shooting film off a television monitor. So, they had these kinescopes that would get bicycled across the country to all these different stations. When Hazel testified in September 1950 before the House Un-American Activities Committee, in spite of the explicit wishes of her husband, who told her you cannot win with these people, she clearly did not understand exactly who she was going up against. She thought she had truth on her side, she had right on her side. That the things that were written about her were untrue and if she could only just say that, then all would be forgotten, and they would go, “Yes, yes, you’re quite right, we’re so sorry,” and she would continue to on with her life. Now we now that’s not what happened. We know that the people who were on the House Un-American Activities Committee were basically in cahoots with the former FBI and ex-military intelligence people who were responsible for writing Red Channels, which smeared so many artists. At the same time, there was a campaign that was being run to put pressure on media that were employing people who had been named in Red Channels as communist sympathizers or as communists. And that campaign was to basically engineer a boycott of sponsors, so Hazel comes back from Washington; she has not achieved the result that she wanted. She goes back into her show, the ratings are good, there is tremendous pressure on this boycott campaign, it’s all part of the same engineered smear campaign. And, within a matter of weeks, the network caves, they fire Hazel and she was told that all of the material from her show, all of the Kinescopes were dumped into the East River and destroyed. It’s like going down a rabbit hole. We went down many, many rabbit holes to see if there was any possible way any of that material could have survived. We talked to archivists, we talked to scholars of the DuMont Network, we talked to a guy in Brooklyn who has a garage full of DuMont Kinescopes. We heard rumors that there were some in an archive in Western Canada, and we set out and scoured those archives. If they’re out there, we couldn’t find them. And at this point, the conclusion has to be that they most likely were destroyed.

When you look at the arc of Hazel’s life and her marriage – two gifted people with strong personalities; it was like she needed to use her gifts and had to travel. They were such a dynamic couple, it seem that marriage could not have survived. What was your takeaway?

SM: They were a very dynamic couple. They were extraordinary both in black and white America in the 1940s and into the 1950s. There was no other black couple like them, if you want, they were the Beyonce and Jay-Z of their day. There was this fusion of the world of culture, the world of politics. They both believed very strongly, to the bottom of their bones, they believed in a better future for their people, they believed in freedom and desegregation, in civil rights. And that was a profound belief. But it wasn’t enough in the end to anchor the marriage. There was a lot of separation, Adam, her husband, asked her to give up nightclubs because in his other role, he was the pastor of the Abyssinian Baptist Church, which was the most important Baptist church in the Americas at that time. Ladies of the church, in particular, did not appreciate having a night club chanteuse as the first lady of the church. And so Adam asked her to give up clubs and in giving up clubs she left a life in New York and went on the road basically, and toured. And that caused stresses. His own commuting to Washington caused stresses. She hated Washington. He found a way to both preach and make Washington work for him, she couldn’t stand Washington. She hated the segregation. She hated the reminders of all of that, she hated the fact they couldn’t go to a restaurant and get a meal. It was ridiculous. She just felt it was being thrown in her face all the time. So that didn’t help [the marriage] because she really limited the time that she spent there. And Adam was a bit of a rogue, let’s face it. He had a roving eye, he was very charismatic. There were always, people, women in particular hanging off him. And she found that tiresome and she was ferociously independent. She had been a bread winner since the age of 15, and by the age of 19, she was the major bread winner in her family. She was taking care of her mother and grandmother. She was the one who was largely putting food on the table.

Jazz pianist Jason Moran was great – he showed how intricate her piano playing was because he couldn’t keep up. Was it hard to find people to interview who knew who she was and could speak about her?

SM: Well as you hear in the film, there were other musicians, Camille Thurman is one, Mickey Guyton is another, who’d go, “Who the heck is this person and why have we never heard of her and thus the title of the film, “The Disappearance of Miss Scott.” Adam told a story that I wish we had known about, but it happened this summer, well after we had finished filming – I think it’s called the World Orchestra in Miami; they put on a Hazel Scott event. And using A.I., they were able to finally put onto paper what it was that she had actually played. And you notice in most of those clips, she’s not focused on her hands, she not looking at the keyboards. She’s looking at the camera, she’s looking at the audience, she’s smiling. One of the musicians who was playing in this Hazel Scott concert basically said – it’s like being in the Olympics. It’s incredibly difficult. And in our film Tammy Kernodle, whose a musicologist, professor, somebody who really knows her way around musicians, she talks about Hazel in terms of virtuosity. She says virtuosity is not often a word applied to female pianists or female musicians, and that Hazel was virtuoso.

I was wondering if you wanted to include Alicia Keyes, since she brought Hazel’s name to a larger audience at the Grammy’s.

SM: When we were in production it was A) Covid, B) she was getting ready for a tour. Then she was recording, so it didn’t go very far.

Throughout the filmmaking process, how did you grapple with the reality of what she was up against—not just as a Black woman in America, but as someone unafraid to challenge the status quo? From where do you think that fortitude and courage came?

SM: We’ve talked a little bit about her character. Very early in the film, Adam refers to a photograph of her at age of three, and he says, “It’s all there, I’m here, deal with me.” There were stories in her memoir that we could not include for reasons of time, where she talks about her own battles with herself and her own constant curiosity. By the time she died, and very early on in her professional career, Hazel was reading and speaking and singing in about seven different languages.

I wondered about that – how did she know French so well?

SM: She learned French early on, and then of course, she went and lived in France. She gave concerts in Tel Aviv in Hebrew, she spoke Italian, she spoke Portuguese, she spoke Spanish. She was a real polyglot, which of course I think speaks to her intelligence and her curiosity. You asked about her character and her fortitude, and I think there are many examples of extraordinary women doing unexpected things. If you want to, look at Harriet Tubman as an example. I was reading a story in a British paper the other day about the woman who discovered how the helix really was formed, and of course her name was erased from history. Hazel’s story is not that uncommon in that she did disappear.

I interviewed Madeleine Hetherton-Miau the producer of the documentary Mozart’s Sister, and women still disappear, even though we’re in more of an equal time period between men and women.

SM: Yeah, I think that’s very true

What made her move back to the States finally since it seemed like Paris accepted her and she was happy there?

SM: She was very happy in Paris. And her son lived with her, he went to school there, spent summers with his father; he had this bi-continental life. And a time came when things got tougher, music had moved on, there wasn’t as many gigs available. She could no longer fill the great big halls like the Salle Pleyel, in Paris, or the Palladium in London. Economically it was harder, and her son basically said, “It’s time for you to come home. It’s time.”

Was there a longer version or will there be an extended version?

SM: I don’t know where we would put a longer version, frankly. A PBS hour and a half is 82, so that’s where we ended up. I think for a festival screening or for any other kind of screening, I think an hour and a half is a good length.

When I saw the film’s credits, I remembered your name as a network TV news correspondent and was like, “Oh that’s where she went!” How did this project come about? Any others in the production pipeline?

SM: There are other projects in the pipeline, which I can’t talk about yet. 4th Act came about – I was asked to work as an executive producer on a documentary about the history of news and that was a big multi-part documentary series, which in the way that often happens whether on a film or documentary production, kind of fell apart at the last moment over financing issues; we were not the ones raising the money. For Hazel, we raised the money, we brought in the money and that’s no mean feat in this climate.

When I interview people, its always – how did they get funding for a PBS project, and I did notice you had a lot of funding, and I did wonder how difficult that process was?

SM: Getting a full commission, meaning you’re fully funded from PBS is just not possible, that’s just not the way they operate. And that’s very true of a lot other broadcasters as well. So you end up having to go to all these different pockets to make your case. The NEH was a very generous funder, ITVF, Black Public Media, the Better Angels society, PBS itself, all of them were very, very generous and we are incredibly grateful for all of their support. Plus, we then made a very conscious decision, which a lot of film makers are making, which was take our post-production fully into Canada, to partner up with a Canadian production company in order to claim Ontario and Canadian tax credit. And a lot of companies are doing that, there’s a reason why that industry is growing in Canada; the side effect of that, from the Canadian prospective, is that it has developed a really skilled workforce.

All the rare footage you used, was it hard to find?

SM: Some of that stuff, it’s relatively easy to go the people who hold the Ed Sullivan archive, for example, they’re very organized, they know exactly what they’ve got, they can tell you in a matter of 24 hours what they’ve got. It’s more difficult trying to track down some of these other things – who’s got the rights to that? Who holds that? Where would we find that? You kind of start off as a big black hole labeled “archive” and then you have to populate it. And material comes from all kinds of places and sometimes it comes from very surprising places.

Given the challenges of working on documentary films, what keeps you going and doing this?

SM: I love the work. I love the creative process, I like the stories. Fourth Act Factual, actually, is my company, we do only what we want to do, and that we can sell (laughs). But we don’t take on stuff that we’re not interested in or isn’t right for us. And my partnership – I live in France, one of my partners lives in Rome and the third lives in Athens; we don’t care where people live. I think Covid taught us as that it doesn’t really matter, as long as you share some common values and share common goals, you can make it work. And we do make it work. We partner up with people all over the place, we have a partnership currently with a production company in Mexico, we have another partnership with a production company in Montreal, we have another partnership with a production company in the UK. And as I said, we did all of the post for Hazel in Canada and we did it all by remote control. And there are tools now that will let you literally be in the edit room with the editor in real time, and that changes the way things work. It often is better to be in the same room, but if it’s too complicated or it’s too expensive, or you just can’t make it work for some reason, there are ways around that.

Is there anything you want to say about Hazel that you learned, or that you think people should know about her story, or the documentary?

SM: Adams’s last words in the film were, he says his mother always said to him, “If you’re right, don’t back down. If you’re right, don’t back down.” And if you’re right, she’s right – don’t back down!

[This interview has been edited for length and clarity]

To learn more about the documentary film, or to see a timeline of Hazel Scott’s life, visit the American Masters website.

To learn more about Sheila MacVicar and her production company 4th Act Factual, visit 4thact.com or follow Sheila on her X/Twitter account.

KLCS|Passport members can stream The Disappearance of Miss Scott on demand on the PBS App or online at: watch.klcs.org.